Dean

Dean’s Story: A Life Lived Fully, with a Shunt and a Smile

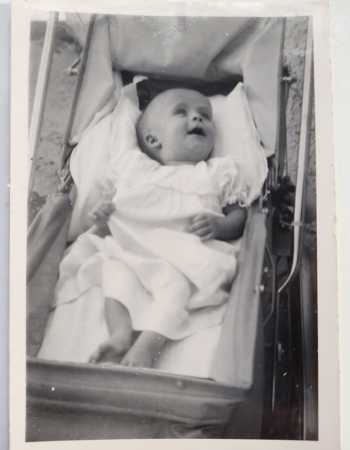

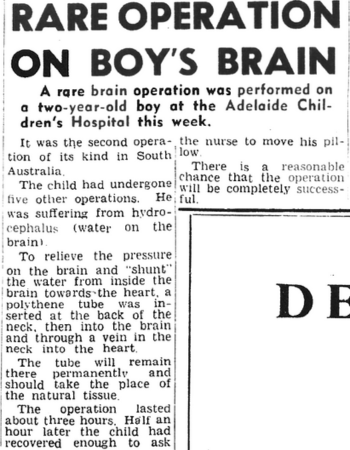

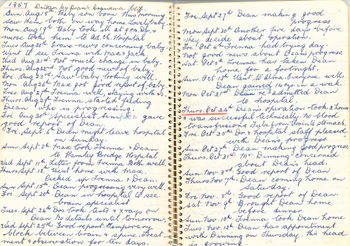

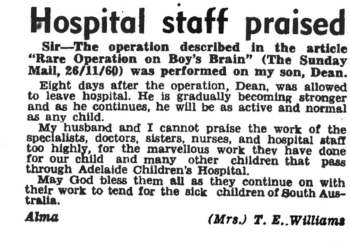

Dean Williams was just nine weeks old when he had his first operation. Diagnosed with hydrocephalus — a condition where excess fluid builds up around the brain — his parents were told the outlook was grim. It was 1957, and treatment was still in its early, experimental stages.

Placing their trust in pioneering neurosurgeons Mr Donald Simpson and Mr Trevor Dinning, Dean’s parents gave consent for whatever was needed to save their son’s life. He would go on to receive one of the first paediatric shunts in Australia — a medical device designed to drain excess fluid from the brain and redirect it elsewhere in the body.

Thanks to Dean’s grandmother, who lovingly kept a handwritten diary of every hospital admission and operation, we now have an extraordinary account of his medical journey. In total, Dean would undergo 19 operations. Her notes, faithfully updated throughout Dean’s childhood and teenage years, provide a rare insight into evolving treatments — and the strength of a family navigating an early life shaped by hospital corridors and uncertainty.

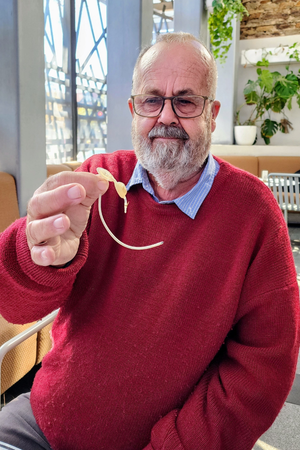

Today, Dean turned 68, making him the longest surviving person in Australia with a paediatric VA shunt.

“One of the lucky ones”

Dean is quick to count himself fortunate. “One of the nurses told Mum and Dad to go home and have another child — that I wouldn’t be here in the morning,” he recalls.

He remembers hearing of another baby born at the same time, whose family initially refused surgery. When they saw Dean’s improvement, they changed their minds — but it was too late. The raised intracranial pressure had already caused significant brain damage leading to lifelong disabilities.

Shunt procedures have advanced remarkably since Dean’s early surgeries. “These days, they put the shunt in and coil it up so it unravels as the child grows,” he explains. “With me, they had to open up my neck every time I grew and add a bit more hose.” Surgeons first attempted to drain the fluid into the stomach, but that led to blockages. The next option — the kidney — failed too, damaging the organ. Eventually, they redirected the fluid to his heart. “I’m sure I caused the doctors and my parents many sleepless nights.”

When Dean’s parents told his grandfather about the plan to connect a tube from his brain to his heart, his response was classic. “Don’t let them do that — he’ll get the hose hooked up!” Dean laughs. “He imagined it running across the back of my shoulders.”

Living beyond limitations

Dean grew up on a farm in Hamley Bridge, South Australia. He remembers countless trips back and forth to Adelaide. “Mum and Dad were always running me down to the Children’s Hospital,” he says. “I remember a few times the shunt was blocked, but by the time we arrived I felt alright. Dad suggested perhaps it was the vibration from the rough country roads that cleared the blockage.” Doctors kept him in for observation — and within 36 hours, the shunt had blocked again. “So Dad might’ve been right.”

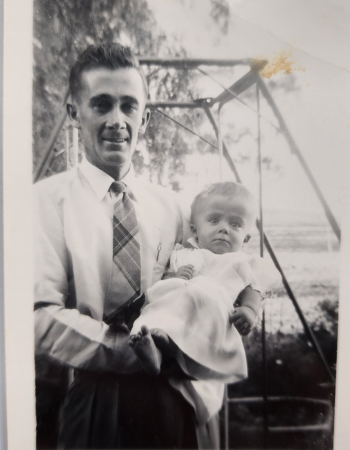

Pictured: Dean just a few months old with his Dad Max

These regular hospital runs inspired Dean’s parents and a friend to start the first ambulance service in town.

After an infection led to meningitis, Dean was left with significant hearing loss, but recent medical advances have helped. “I had a cochlear implant about nine months ago. Interestingly, it also helped reduce the unexplained headaches I was getting — maybe cutting through all the old scar tissue relieved some of the pressure.”

In 1972 the family moved to Hoyleton. School wasn’t easy. “Because I was deaf, the teachers thought I was dumb,” Dean says. “My hearing aids were the size of golf balls, and I had no balance — I couldn’t run to save myself, so I got picked on. I didn’t play any contact sports to protect what was left in my head. Dad offered some classic advice, he would say ‘if you’re playing sport on the weekends, you haven’t been working hard enough during the week.”

So Dean worked around the farm, learning to drive at just 8 or 9 years old. He got his drivers license at 16, a truck license at 17, and took over the family farm at 21. He has lived a full, independent life, and credits a group called Rural Youth with helping bring him out of his shell and giving him the opportunity to travel. Offering camps, competitions and training courses, he made lifelong friends who he still catches up with regularly some 40 years later. Dean retired at 54 due to poor balance and constant headaches, which he believes were likely due to stress. Now retired, he still loves to travel and enjoys a good laugh, good company, swimming and his latest hobby - photography. “It’s something I do just for me,” he says. “It’s non-stressful, and I’m not competing with anyone.”

“After all that surgery…”

Dean still carries a question mark shaped scar, but one of his non-surgical scars might surprise you.

“They would give us fairy bread and cocoa with 100s and 1000s on top to try to get some nutrition into us. To this day, I can’t stand the stuff!”

Dean’s connection with his childhood neurosurgeons, continued well into adulthood. He fondly recalls a chance encounter with Professor Donald Simpson during his final shunt-lengthening surgery.

“I was walking down the passage at the Royal Adelaide and saw him coming the other way,” Dean says. “I hadn’t seen him in years. I said, ‘Oh, you’re Mr Simpson.’ He corrected me — ‘Professor Simpson now.’”

They sat and talked for 20 minutes. A nursing sister scolded Dean afterward: “You don’t just walk up to Professor Simpson like that!” But the next day, Professor Simpson walked into Dean’s room and said, in front of that very nurse, “You’re going home tomorrow, and I’m really glad you stopped and had a yarn yesterday.”

Later, at a fundraiser for the Neurosurgical Research Foundation, they caught up again. Professor Simpson was studying ancient history and showed him a photo riding a camel near the pyramids in Egypt with a pith hat on. He asked Dean about life on the farm.

“When you muster the sheep, do you use a horse or motorbike?”

“I use a motorbike, sir,” Dean replied.

Simpson leaned in. “I trust you wear a helmet?”

“No,” Dean confessed. “Matter of fact, I don’t.”

Simpson looked at him and said, “Dean, after all that surgery — you are a slow learner.”

Dean smiles, “I told him, ‘I’d rather fall off a motorbike without a helmet than off a bloody camel.’ He looked at me and said, ‘I take your point, son, I hadn’t thought about that, a pith hat wouldn’t save me!”

A message for others

Dean is living proof that pioneering surgery, persistence, and a bit of humour can carry you through even the toughest beginnings. His advice to others facing neurosurgery — whether patients or parents — is heartfelt and generous:

“Have faith in your doctors. Let them think outside the square. I’ve lived a pretty normal life. I’m very thankful to Mr Dinning and Professor Simpson — and their apprentices — for what they’ve done.”

Pictured: Dean today with one of his old shunts